Research - American Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health (2022)

Hospital Ethics Committees in Japan: Current Status From an Exploratory Survey 2012-2015

Yuri Dowa1,2, Yoshiyuki Takimoto3*, Masahiko Kawai2 and Takashi Shiihara42Department of Neurology, Gunma Children’s Medical Center Shimohakoda, Gunma, Japan

3Department of Pediatrics, Kyoto University, Graduate School of Medicine Shogoin-Kawahara-cho, Kyoto, Japan

4Department of Biomedical Ethics, The University of Tokyo Congo, Hongo, Tokyo, Japan

Yoshiyuki Takimoto, Department of Pediatrics, Kyoto University, Graduate School of Medicine Shogoin-Kawahara-cho, Kyoto, Japan, Email: takimoto@m.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Received: 25-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. AJPMPH-22-62423; Editor assigned: 27-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. AJPMPH-22-62423 (PQ); Reviewed: 13-May-2022, QC No. AJPMPH-22-62423; Revised: 18-May-2022, Manuscript No. AJPMPH-22-62423 (R); Published: 25-May-2022

Abstract

Background: Hospital ethics committees have gained importance in Japan. But there is no current status report for the last decade.

Aim: To ascertain the status of Japanese hospital ethics committees, to clarify whether the prevalence of such committees differs based on the number of hospital beds, and to identify the requirements for sustaining such committees in practice.

Subjects and Methods: A questionnaire survey was sent to 2,433 hospitals accredited by the Japan Council for Quality Health Care. Results of the questionnaire survey were entered into Microsoft Excel 2010 and subjected to simple aggregation. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Text Analysis for Surveys and Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results: Of the 472 participating hospitals (19.4% response rate), 394 (83.5%) had established/were establishing their hospital ethics committee at the time of the study. The main reason for this was the evaluation of hospital functions by the Japan Council for Quality Health Care. Clinical ethics consultations were performed in 239 out of 394 hospitals (60.6%). A full ethics committee was adopted by 149 out of 239 hospitals (62.3%).

Conclusion: Full ethics committees are common in Japan. Clinical ethics consultations have not yet been recognized as an activity for hospital ethics committees to carry out.

Keywords

Hospital ethics committees; Clinical ethics consultation; Questionnaire; Full ethics committee; Small team consultation

Introduction

The main purpose of clinical ethics is to solve ethical issues related to clinical practice. This field involves identifying, analysing, and solving ethical issues encountered in patient care and clinical research, as well as providing ethics education for health care staff and medical students [1]. Clinical ethics form a part of practice, education, and research. In practice, the activities pertaining to clinical ethics include organizing clinical ethics conferences, conducting clinical ethics consultations—led by clinical ethics specialists—at the request of medical care teams, performing ward rounds focused on ethical issues, etc.

Japanese ethics committees are unique because they act as both research ethics committees as well as hospital ethics committees [2]. Research ethics committees review the ethical aspects of research, while hospital ethics committees engage in discussing ethical issues in individual cases in the medical field [3]. Since the first ethics committee was established at the University of Tokushima, School of Medicine in 1982, the ethics committees have spread rapidly among the university hospitals in Japan. The main reason for the rapid spread was that they had to develop the ethical administrative guidelines concerning medical research [4]. Therefore, hospital ethics committees are considered as research ethics committees in Japan.

Nagao et al. surveyed all resident-teaching hospitals in Japan with a focus on hospital ethics committees in 2004 [3]. The survey response rate was 41.7% and 75.3% of the respondents did not have a hospital eth- ics committee. In 2005, the Japan Council for Quality Health Care—a non-governmental agency that evaluates hospitals—added clinical ethics items to their hospital evaluation instruments for the first time [5]. In the 2009 revision, as part of the evaluation criteria, the evaluation instruments incorporated the establishment of hospital ethics committees and the system of clinical ethics consultations [6]. However, thus far, no survey has identified the extent to which Japanese medical institutions have been able to adopt such practices in the rapidly changing society. This study aims to ascertain the status of the hospital ethics committees in Japan, to clarify whether the prevalence of hospital ethics committees differs based on the number of hospital beds, and to identify the requirements for sustaining hospital ethics committees in practice.

Materials and Methods

A questionnaire survey was conducted to ascertain the status of hospital ethics committees in Japanese hospitals. The questionnaire items were selected based on previous research by Fox, Myers, and Pearlman (2007) and the questions were developed in accordance with the situation prevailing at the time in Japan. The final questionnaire comprised questions on 50 topics based on a prior study by the authors and their research collaborators. There were 31 single answer questions, 18 multiple-choice questions that also included a self-reporting question, and 1 self-reporting question.

The 2,435 hospitals that were accredited and publicly listed by the Japan Council for Quality Health Care as of June 15, 2012, were selected for this study. Excluding two institutions that had closed down, we assigned specific numbers to the 2,433 hospitals. The authors sent request letters for participation in the web-based self-reporting questionnaire survey to these 2,433 hospitals by mail between December 10, 2012 and March 31, 2013. To avoid answering twice, a hospital-specific URL was included in the request letter for participation. The participants answered the questionnaire online anonymously.

Results of the questionnaire survey were entered into Microsoft Excel 2010 and subjected to simple aggregation.

Data from the free answers were also entered in Microsoft Excel 2010. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Text Analysis for Surveys, and Microsoft Excel 2010 was used to aggregate the frequency of occurrence of phrases.

All participants provided informed consent. The study design was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (E1550 2012).

Results

Demographic features

Of the 2,433 hospitals, 472 responded (response rate 19.4%). Of the 472 respondents, 328 (69.5%) were members of their ethics committees. Table 1 shows the demographic features.

| Demographic Category | (n=472) | Background of the Respondents | (n=472) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bed Size 20-99 100-499 ≥500 Ownership |

72(15%)

314(67%) 86(18%) |

Sex Male Female Occupation Medical doctor Administrative staff |

365(78%) 107(22%) 184(39%) 154(33%) 55(12%) |

| Church or temple Non-religious |

18(4%) 449(96%) |

Nurse |

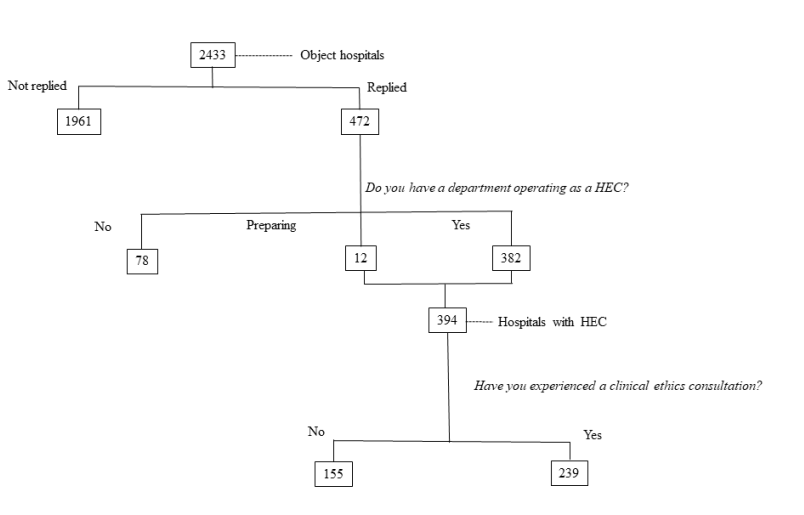

As shown in Figure 1, the 382 hospitals of the 472 hospitals (80.9%) had a hospital ethics committee, and 12 reported that they were preparing to establish it. Among these 394 hospitals, 155 (39.3%) reported operating an hospital ethics committee as an independent organization within the hospital, 33 (8.4%) reported operating it under the research ethics committees, and 19 (4.8%) reported operating it under other departments. The 394 hospitals were asked additional questions on the organizational structure and the actual activities of their hospital ethics committees.

Reason for establishing an hospital ethics committee

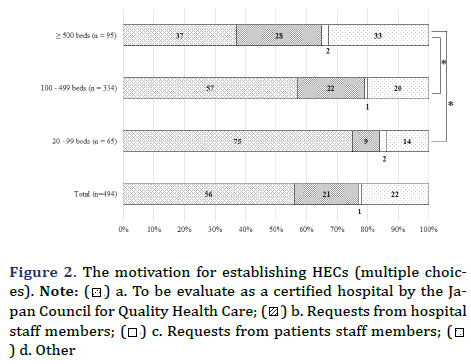

As shown in (Figure 2), the main reason was the evaluation of hospital functions by the Japan Council for Quality Health Care. The smaller-bed-number group (20–99 beds) had higher percentage of the Japan Council for Quality Health Care evaluation than the larger er-bed-number group (100 – 499 beds or ≥ 500 beds). On the other hand, the larger-bed-number group ( ≥ 500 beds) was more likely to choose the reason that requests from hospital staff members compared with the smaller-bed-number group (100–499 beds or 20–99 beds).

General information on hospital ethics committees

The average number of hospital ethics committee members was nine. By profession, the median values for hospital ethics committee members were as follows: three medical doctors, two nurses, two clerical staff, and one individual who was not a hospital staff member (e.g., lawyer, university professor, or representative of the patients’ association).

Roles of hospital ethics committees

The hospital ethics committees clarified that they engaged in multiple roles. In all, 840 multiple-choice answers were provided by 394 hospitals. The hospital ethics committees of 288 out of 394 hospitals (73.1%) engaged in clinical ethics consultations, those of 279 (70.8%) engaged in formulating/updating ethical guidelines, those of 212 (53.8%) engaged in delivering in-service education, and those of 61 (15.5%) provided other services, such as a research ethics board, clinical trials, and organ transplants.

A total of 239 hospitals with hospital ethics committees reported actually conducting clinical ethics consultations, and an additional 49 hospitals reported offering clinical ethics consultations but indicated that they had not performed these consultations as on the date of the survey. The average number of clinical ethics consultation requests in the 239 hospitals was 4.4 cases per year.

Methods of clinical ethics consultations

Various types of clients request clinical ethics consultations. We obtained 779 multiple choice answers from the 239 hospitals. The most frequent types of clients were heads of medical sections (222, 28.5%), other medical staff (197, 25.3%), doctors-in-training (92, 11.8%), patients (59, 7.6%), patients’ families (59, 7.6%), and others (150, 19.2%). The methods of information collection regarding problems were investigated through a multiple-choice question. Of the 551 multiple answers from the 394 hospitals that reported an existing or developing hospital ethics committee, the most popular methods were interviews with the staff (173, 31.4%), medical research ethics committee records (141, 25.6%), and consultation forms (127, 23.0%). Conversely, interviews with patients and/or their families were adopted by 70 respondents (12.7%), and physical examinations by 40 respondents (7.3%).

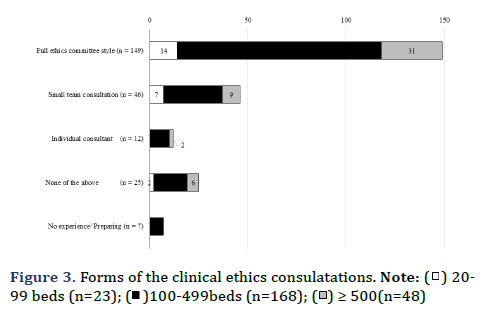

Figure 3 describes how 239 hospitals operated a clinical ethics consultation. We also asked an open question about how hospitals operate their hospital ethics committees. We obtained written answers from 25 employees who answered “none of above.” In the 25 answers, the most common way to operate the hospital ethics committee was reported as altering the number of consultants depending on the cases (13 hospitals). On the other hand, eight hospitals reported that they adopted a small-team consultation and an individual consultant on a case-by-case basis. Of the 223 hospitals that reported using discussions and other methods in the previous question, 201 (90.1%) held discussions to arrive at unanimous conclusions. However, other hospitals did not have face-to-face discussions. They reported that the administrators summarized the opinions of hospital ethics committee members by email or returned all opinions to the clients.

Records of clinical ethics consultations

We asked the 239 hospital ethics committee operating hospitals how the clinical ethics consultation records were maintained in the department through a multiple-choice question. We obtained 262 responses. Among them, 135 (51.5%) reported that they maintained simple records alone, while 101 hospitals (38.5%) reported that they maintained detailed records that included information on the discussion, the course of discussion, and outcomes. The remaining hospitals did not maintain any records in their departments.

We also asked the 239 hospitals about documenting consults in patient’s medical records. While only 59 (24.7%) of the 239 hospitals reported recording the consultation outcomes in patients’ medical records, 104 hospitals, the majority (43.5%), responded that recording the contents of the consultation in the medical records depended on the nature of each case, and 76 hospitals (31.8%) did not create any records. Hospitals in the small-bed-number category were more likely to record the consultation in patients’ medical records (16 of 32 hospitals, 50.0%) than the medium- bed-number category hospitals (32 of 166 hospitals, 19.3%); however, there was no statistical significance. In all, 163 hospitals made note of some details in their medical records. We found that medical doctors were responsible for this task in 108 hospitals (53.2% of the 203 responses), and nurses wrote them in 65 hospitals (32.0%). There were no significant differences between each bed-number group.

Enforceability of the hospital ethics committee recommendations

Of the 239 hospitals, 85 hospitals (36.5%) reported that the clients must comply with the final decisions of its clinical ethics consultation. On the other hand, 148 (63.5%) regarded the decisions of its clinical ethics consultation as recommendations. There were no differences based on the number of beds.

Our inquiry into the follow-up process after the consultation found that 85 hospitals followed up on the outcome of a consultation. The reported follow-up methods were obligatory reporting of detailed accounts (25 of the 142 answers, 16.9%), obligatory reporting depending on the case (69 responses, 48.6%), and tracking subsequent progress (39 responses, 27.5%). The remaining nine responses indicated a choice of other methods.

The person with the ultimate responsibility for consultation cases was the hospital director in 149 responses, which was almost half of the 339 responses.

As we mentioned previously, the 394 hospitals of the 472 hospitals had a hospital ethics committee (Figure 1). But 153 hospitals had never executed clinical ethics consultations. We asked them why they did not undertake any clinical ethics consultations with the three multiple-choice questions and the open question (Table 2). We obtained the answers from 50 hospitals and 22 free-form descriptions. We conducted a text analysis on the contents. The results revealed six categories shown in Table 2.

A Problems with the system (MCQ) |

||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | I do not know |

18 |

| 2 | It is a new system |

16 |

| 3 | The answers cannot force the clients to do so |

10 |

| 4 | It takes a long time for the clients get answers |

4 |

B Problems with the consultants (MCQ) |

||

| 1 | Lack of knowledge and experience |

18 |

| 2 | I do not know |

14 |

| 3 | They do not have enough time and money for training |

9 |

| 4 | The HEC cannot take responsibility for the results |

8 |

C Problems with the clients (MCQ) |

|

|

| 1 | Staff, patients, and their families do not know about the clinical ethics consultation system |

27 |

| 2 | They will not consult other department staff (they want to resolve the matter themselves) |

13 |

| 3 | They are not aware of ethical issues |

12 |

| 4 | They do not trust the clinical ethics consultation process |

11 |

| 5 | I do not know |

8 |

Opinion (Open answers) |

||

| 1 | Staff, patients, and their families are not concerned about ethical issues |

10 |

| 2 | Other departments deals with ethical issues |

7 |

| 3 | We have no ethical issue |

6 |

| 4 | We have not completely established our clinical ethics consultation system |

4 |

| 5 | Ethical problems are not reported to their HEC |

2 |

| 6 | Our hospital guidelines can solve ethical issues |

1 |

Self-evaluation

In response to the request for self-evaluation of their hospital ethics committee, 90 (19.1%) of the 472 respondents reported sufficient, 270 (57.2%) reported insufficient, and 112 (23.4%) responded that they did not know.

There were three principal reasons for considering their hospital ethics committees sufficient. First, a system for scrutiny was already in place as a result of multidisciplinary external resources. Second, they assessed subjectively that their hospital ethics committees worked effectively. Third, their hospital ethics committees were functioning sufficiently because they had a few consultations each year.

We got 187 responses of the 270 hospitals considered their hospital ethics committees as insufficient. The most-reported reason was inadequate system/ response capabilities (100 respondents, 53.5%), followed by the lack of staff knowledge/interest (35 respondents, 18.7%). The third most-reported reason, provided by nine people (4.8%), was the limited number of consultations.

The reasons for choosing the option “I do not know” included the following: First, they did not have enough knowledge to evaluate whether their hospital ethics committees were sufficient. Second, it was difficult to draw comparisons with other institutions. Finally, they had no experience with clinical ethics consultations.

The open descriptions revealed the difficulties encountered in conducting and administering clinical ethics consultations. Therefore, we categorized and counted the opinions from the open-ended questionnaires. We obtained 211 responses from 106 hospitals in all. The most-reported problem (62 responses) was “how to disseminate information about the existing clinical ethics consultation system,” followed by “how to provide a platform for fair discussions” (53 responses), and “how to identify latent ethical problems” (48 responses).

Discussion

This was the first status survey to have been undertaken since the hospital ethics committees were incorporated as a constituent item in hospital function evaluation in Japan. Before 2005, only 17.5% of medical school ethics committees and 32.2% of hospital ethics committees were involved in clinical ethics consultations [2]. In 2004, 66 out of 640 hospitals each had a hospital ethics committee [3]. In this study, 382 of 472 hospitals each had an hospital ethics committee, and 12 hospitals were preparing to establish their hospital ethics committees. Although we cannot simply compare this with the previous study, we may infer that hospital ethics committees have become popular in Japan.

This study revealed that only 24% recorded consultations in their medical records in Japan, while 72% of the respondents always documented their consultations or details in medical records in the United States [7]. The remaining respondents (76.0%) either did not enter details of consultations in medical records or did so only in specific cases. This indicates that the status of the hospital ethics committee is not officially endorsed in Japanese hospitals yet, and its function is most likely treated as an informal activity.

This study’s results suggested that clinical ethics consultations in Japan aim to reach unanimous conclusions as determined in a previous study [3]. There are two main reasons for this tendency. First, ethics committees began as an ethical review board for medical research and later developed into a committee that performed the functions of both hospital ethics committee and research ethics committee. Second, there was a shortage of clinical ethicists in Japan. Fox et al. reported that small-team models were significantly preferred by clinical bioethicists, and full committee models were adopted by hospital ethics committees without well-educated staff [7]. These trends were likely to apply to Japan.

In 2004, only 25% of hospitals had hospital ethics committees, but 89% of hospital administrators recognized the need for hospital ethics committees. In this survey, 81% of hospitals had hospital ethics committees, and 76% of respondents considered hospital ethics committees necessary. This means that the participants in this survey were highly interested in hospital ethics committees.

On the other hand, 57% of hospitals perceived their hospital ethics committees as insufficient. One of the reasons was the lack of ethical knowledge. To compensate for the lack of medical ethics education, many postgraduate education programs have been held, including clinical ethics seminars sponsored by the University of Tokyo’s clinical ethics project [8], clinical ethics introductory lecture courses sponsored by Kyoto University [9], and debriefing sessions in hospitals. Furthermore, the multi-centered volunteer-based small-team ethics consultation by Prof. Asai et al. has continued for more than ten years [10,11]. This tele-consultation system has continued thus far possibly because the medical ethics education problem has not been resolved yet and there is still a lack of clinical ethics consultants. This study is the first investigation into how hospital ethics committee members gain the required knowledge and skills.

This survey revealed that the evaluation of hospital functions by the Japan Council for Quality Health Care significantly influenced the motivation for establishing hospital ethics committees. No previous study has reported on reasons for establishing hospital ethics committees. This trend was observed in hospitals with 20- 99 beds and 100-499 beds, but not in hospitals with 500 or more beds. Large hospitals tend to have more medically and socially complicated cases requiring multifaceted care [12]. It is still not clear which department should be responsible for clinical ethics consultations and what experience the committee members should have in order to facilitate it. This is because each of Japan’s hospitals has attempted to develop its own system [13].

This study has several limitations. First, the low response rate may cause self-selection bias. The respondents may be highly interested in clinical ethics. Although the number of respondents is small, the results are based on their actual experiences. There are no previous studies on the activities of Japanese clinical ethics consultants.

Conclusion

Considering that there have been no reports on the spread and activities of hospital ethics committees in Japan, we could consider this paper as an exploratory study. This study can facilitate a better understanding of the current situation and can help clarify future challenges.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participants who engaged in this study

Declarations

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) under Grant JP24610003. No potential conflicts of interest are reported by the authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors have no conflicts of interest.

Code Availability

Results of the questionnaire survey were entered into Microsoft Excel 2010 and subjected to simple aggregation.

Data from the free answers were also entered in Microsoft Excel 2010. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Text Analysis for Surveys, and Microsoft Excel 2010 was used to aggregate the frequency of occurrence of phrases.

Consent for participation and publication

All participants provided informed consent and agreed with publication.

Ethics Approval

The study design was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (E1550 2012).

Availability of Data and Materials

The data will not be deposited on any repositories. But we can share our research data as request.

Authors Contributions

YD contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection, conducted the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. YT and MK contributed to the conception and design of the study, helped to draft the manuscript, and supervised the whole study process. TS critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Core Competencies for Healthcare Ethics Consultation

- Akabayashi A, Slingsby BT, Nagao N, Kai I, Sato H. An eight-year follow-up national study of medical school and general hospital ethics committees in Japan. BMC Med Ethics. 29; 8:8

- Nagao N, Takimoto Y, Akabayashi A. A survey on the current state of hospital ethics consultation in Japan. J Japan Assoc Bioeth. 2005;15:101–6. [Crossref]

[Google scholar][PubMed]

- Fukatsu N, Akabayashi A, Kai I. The current status of ethics committees and decision making procedures in general hospitals in Japan. J Japan Assoc Bioeth. 1997;7:34–9.

- An eight-year follow-up national study of medical school and general hospital ethics committees in Japan

- Crossref

- Fox E, Myers S, Pearlman RA. Ethics consultation in United States hospitals: a national survey. Am J Bioeth.2007;7:13–25.

- Akabayashi A. Interdisciplinary Bioethics Research in Japanese and English. Center for Biomedical Ethics and Law Report. University of Tokyo Center of Biomedical Ethics and Law. 2019; 1: 1-36.

- Kodama S. Introductory Course in Clinical Ethics, Center for Applied Philosophy and Ethics. Kyoto University. 2020;

- Fukuyama M, Asai A, Itai K, Bito S. A report on small team clinical ethics consultation programmes in Japan. J Med Ethics. 2008; 34:858–62.

- Asai A, Kadooka Y, Miura Y, Aizawa K, Enzo A, Ohkita T et al. Hospital Ethics Committee Consultant Liaison. Medical ethics. 2016;

- Bishop JP, Fanning JB, Bliton MJ. Of Goals and Goods and Floundering About: A Dissensus Report on Clinical Ethics Consultation HEC Forum. 2009; 21:275–91. [Crossref][Google scholar]

[PubMed]

- Asai A, Itai K, Shioya K, Saita K, Kayama M, Izumi S. Qualitative Research on Clinical Ethics Consultation in Japan: The Voices of Medical Practisioners. Gen Med. 2008;9:9.

[Crossref][Google scholar][PubMed]

Copyright: © 2022 The Authors. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

) a. To be evaluate as a certified hospital by the Japan

Council for Quality Health Care; (

) a. To be evaluate as a certified hospital by the Japan

Council for Quality Health Care; (  ) b. Requests from hospital

staff members; (

) b. Requests from hospital

staff members; (  ) c. Requests from patients staff members; (

) c. Requests from patients staff members; ( ) d. Other

) d. Other

) 20-

99 beds (n=23); (

) 20-

99 beds (n=23); ( )100-499beds (n=168); (

)100-499beds (n=168); ( ) ≥ 500(n=48)

) ≥ 500(n=48)